New Study by Professor Miller-Struttmann and Mizzou Professor Candace Galen Links the Decline of Alpine Bees to Climate Change

August 18, 2022

A new study by Webster University Biology Associate Professor Nicole Miller-Struttmann,

University of Missouri at Columbia Professor Emerita Candace Galen and University

of Missouri PhD student Zack Miller has identified a critical piece of the puzzle

for a question that has troubled scientists tracking biodiversity as the climate warms

— why are once abundant species declining?

A new study by Webster University Biology Associate Professor Nicole Miller-Struttmann,

University of Missouri at Columbia Professor Emerita Candace Galen and University

of Missouri PhD student Zack Miller has identified a critical piece of the puzzle

for a question that has troubled scientists tracking biodiversity as the climate warms

— why are once abundant species declining?

Their study, compiling many years of observation from three peaks in the Rocky Mountains, found that at high elevations above timberline — referred to as "alpine" regions — bumblebees are losing ground in a process that reflects their low tolerance to warming temperatures. As the alpine climate warms, colonizing bumblebees from lower elevations thrive, potentially displacing alpine resident species. If the trend continues, populations of the alpine bumblebees could become extinct, and soon.

"We predict the local extinction of species in areas where the alpine bees can't migrate further upslope, where the weather is cooler and the growing season still remains short," Miller-Struttmann said. "They are not responding to the temperature changes fast enough because they are stuck in an evolutionary trap."

To grasp the issue, one must understand how alpine bumblebees have adapted over millenia to high elevation living. Because temperatures have historically been very cold at high elevations, the summer growing season has been short. Alpine bumblebees likely adapted by packing their foraging activity and reproductive phase into a rapid burst that now misses out on flowers at later times in a longer, warmer season.

Lower-elevation bumblebees are more flexible in their foraging schedules and have moved upward with climate change. Their more opportunistic habits allow them to exploit resources that their alpine relatives miss out on.

And here's the big problem — the alpine bumblebees are "stuck in a rut" because of the way they have been programmed by evolution. These high-elevation species still only collect nectar and pollen from flowers during a short time period that was the normal growing season in high elevations 50 years ago.

In other words, alpine bumblebees are being heated out of their homes and replaced by subalpine bees with more flexible life history schedules.

"As the climate warms and becomes more variable, organisms specialized to past conditions are declining, be it bumblebees or penguins," Galen said. "We are losing biodiversity at a rapid clip, and with it the ecological services, including pollination services that enrich and sustain our lives."

The study was launched in 2012 and completed this year. In it, the professors looked

at 60 years of data regarding alpine plants and bumblebees in the Colorado Rocky Mountains.

The study was launched in 2012 and completed this year. In it, the professors looked

at 60 years of data regarding alpine plants and bumblebees in the Colorado Rocky Mountains.

The study,"Climate driven disruption of transitional alpine bumble bee communities," was published by the Global Change Biology Journal through the Wiley Publishing Company. Funding was provided by a pair of grants from the National Science Foundation, the Mountain Area Land Trust, the University of Missouri and Webster University.

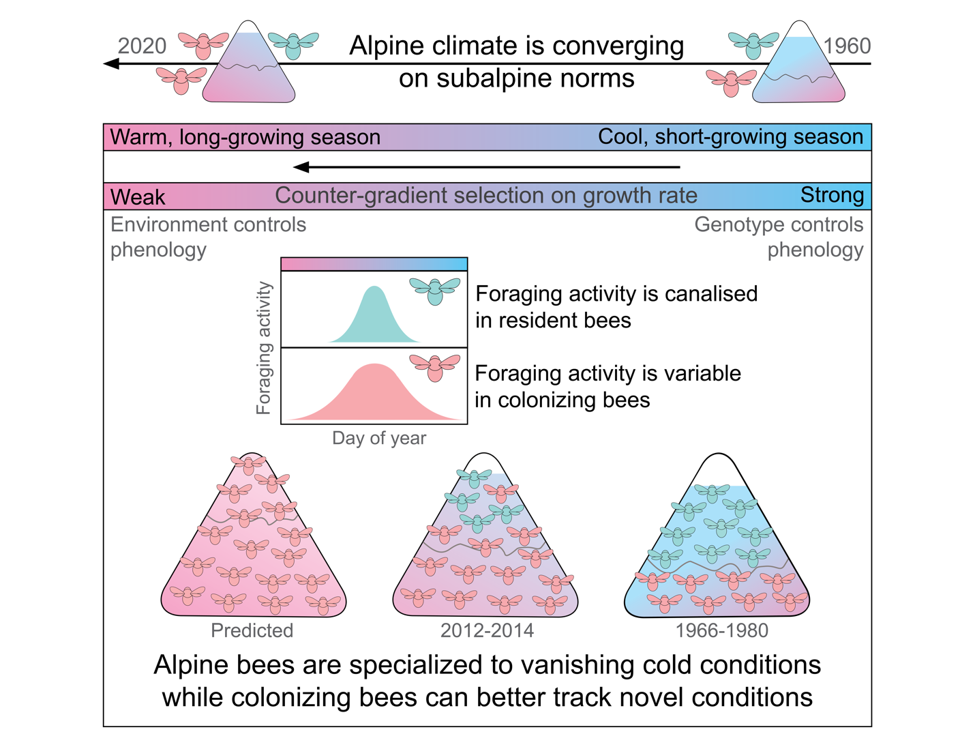

Graphical Summary:

In the Rocky Mountains, range-expanding species are colonizing high elevations. This process, coupled with warming, impacts alpine bumblebee communities. Results suggest that outcomes depend on species' evolutionary histories. Foraging phenology is more canalised in alpine bees, consistent with past selection for rapid resource acquisition. Conversely, the broader phenology curves of range-expanding bees favor access to floral resources over more of the growing season. Range-expanding species increase in abundance with temperature, while alpine residents decline. If trends continue, alpine bumble bee communities will likely lose more specialized residents.

About Miller-Struttmann

Miller-Struttmann is the Laurance L. Browning, Jr. Endowed Professor in Biological Sciences in Webster University's College of Science and Health. She was hired in 2016 after teaching at State University of New York (SUNY). She holds a bachelor's in science from Loyola University and a PhD in Ecology, Evolution and Population Biology from Washington University St. Louis.

During her time at Webster, Miller-Struttmann has made national news for her work in tracking bees through sound, the impact climate change has had on bees, research into beehive collapse, and bee behavior during solar eclipses. Her work was featured in Smithsonian Magazine.

She also has engaged the public with science. Miller-Struttmann helped create the Shutterbee Citizen Science Program, which trains volunteers on how to photograph and identify various bee species in the region and then catalog them in a database that is shared by several universities. She also helped create the pollinator garden with the St. Louis Public Central Library and has worked with fifth and sixth graders and their science teachers in the area to teach the students the fundamentals of field research. In 2019, she was named the 2019 Science Educator Award by the St. Louis Academy of Science.

To learn more about the science programs offered at Webster University, visit www.webster.edu/science-health.