Rediscovering Vada Lee Easter and the Movement to Desegregate Webster

February 01, 2024

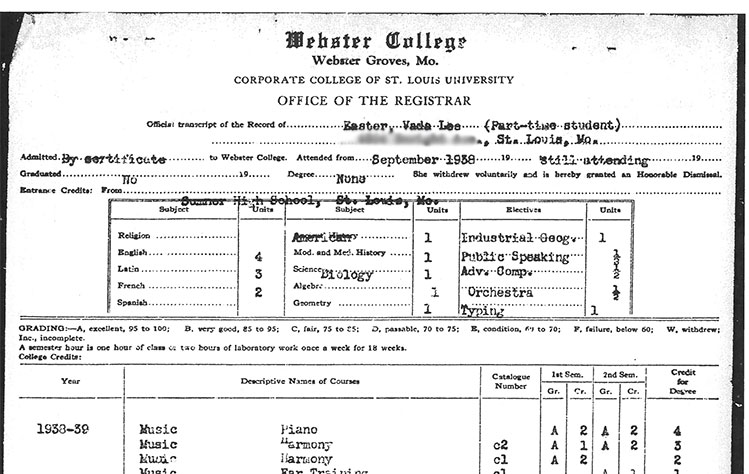

Photo: Vada Lee Easter's transcript as retrieved from Webster University's record

archives.

Photo: Vada Lee Easter's transcript as retrieved from Webster University's record

archives.

Saint Louis University (SLU) has long been credited as the first university in Missouri

to desegregate. According to history books, SLU started admitting Black students in

the summer of 1944. It was the first all-white institution of higher education in

Missouri — and the first in a previous slave state — to integrate its classrooms.

Webster University, history books say, was the second in Missouri when it enrolled

its first two Black students in 1947, Irene Thomas and Jeannette Jackson. Both graduated

in 1950.

Saint Louis University (SLU) has long been credited as the first university in Missouri

to desegregate. According to history books, SLU started admitting Black students in

the summer of 1944. It was the first all-white institution of higher education in

Missouri — and the first in a previous slave state — to integrate its classrooms.

Webster University, history books say, was the second in Missouri when it enrolled

its first two Black students in 1947, Irene Thomas and Jeannette Jackson. Both graduated

in 1950.

That history is now being scrutinized.

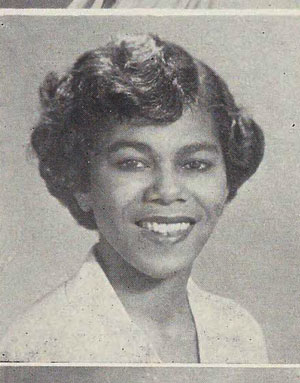

Photos: Irene Thomas (top) and Jeannette Jackson from the 1950 Webster College yearbook.

Newly uncovered records show that Webster University allowed Black students to enroll and study alongside white students nearly a decade earlier before official desegregation policies were announced. Webster wasn’t alone. Other records show that SLU and Maryville University also enrolled Black students decades before they announced the desegregation of their campuses.

These revelations demonstrate how much of the Black experience is misunderstood, misconstrued or simply forgotten, academics and experts say. As a result, even answering a simple question such as when colleges in Missouri began enrolling Black students can be difficult to answer because the information is incomplete.

“The fact is, Black history has often been discredited, discarded and buried and, therefore, we really do not have a complete picture of the Black experience in the United States,” said Webster University Associate Vice President of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Vincent C. Flewellen. “This new information was openly reported in numerous newspapers in the region, yet it never made it to the history books because those books were mainly written by people who had no investment in the health and wellbeing of the Black community. This is a disservice to everyone, not just the Black community, because it ends up misinforming instead of giving us a clearer picture of not only Blacks’ history but of the history of the U.S.”

The Official Record

These facts are not in dispute: The public pressure to desegregate institutions of higher education in St. Louis started in the 1930s, with members of the community publicly calling for a policy change. In 1942, Charles Anderson held a protest on SLU’s campus to change its admissions policy. Then in 1943, Webster University — then called Webster College — officially admitted Mary Aloyse Foster, a local Black student, but was forced to withdraw her admission after Archbishop John J. Glennon ordered the Sisters of Loretto not to admit her, saying “the time was not opportune,” written records show.

Spurred on by Anderson’s protests and letters to the editors decrying segregation, Father Claude Heithaus made numerous public statements against segregation policies during student masses at SLU, creating tremendous public pressure for the University in spite of the well-known views of Glennon. Within a year of Heithaus’ public campaign to change SLU’s policy, Glennon’s letter to the Sisters of Loretto demanding the expulsion of Foster was made public by a local newspaper, further adding to the pressure to end segregation. The campaign worked. SLU desegregated in 1944, starting with its summer courses that year.

Because of his defiance to Glennon, Heithaus was reassigned and ordered to “do penance” for his views. But the tides quickly changed after that. Glennon was named a Cardinal in 1945 and died three months later. Archbishop Joseph Ritter of Indianapolis was named his replacement. Having already desegregated the parochial schools of Indianapolis in the late 1930s, Ritter ordered the desegregation of all Catholic institutions in St. Louis in 1947, eight years before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in “Brown vs. The Board of Education” that segregation was illegal. The Catholic institutions in St. Louis at the time were Webster, SLU, Maryville University (then Maryville College) and Fontbonne University (then Fontbonne College).

Shortly after Ritter’s announcement, Webster became the second institution in Missouri to desegregate. Jeanette Jackson and Irene Thomas would both be admitted to Webster in 1947 and would graduate in 1950, becoming its first Black alumni.

But a research project conducted by a local professor has uncovered newspaper articles that show the change was much more subtle and started decades earlier than what the history texts say, and official records show that Webster, SLU and Maryville had already officially enrolled Black students before they announced policies of desegregation.

The Research

Annie Stevens, PhD, a professor of religious studies at Webster University and a member of the Sisters of Loretto, uncovered records that raised questions about when colleges in Missouri began enrolling Black students. “It happened as part of my research for a larger Loretto Roots/Enslavement research project,” she said.

“This led me to check historic newspapers on the local history of desegregation at Nerinx Hall and Webster, which officially happened after Cardinal Ritter's edict that desegregated all Catholic schools in 1947,” Stevens said. “And that of course matches what we have known about the first officially matriculated African American students at Webster who graduated in 1950.”

The New Information

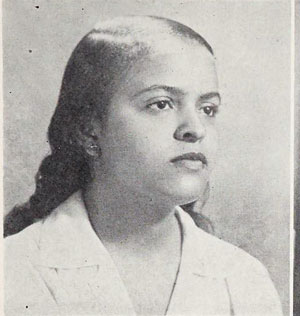

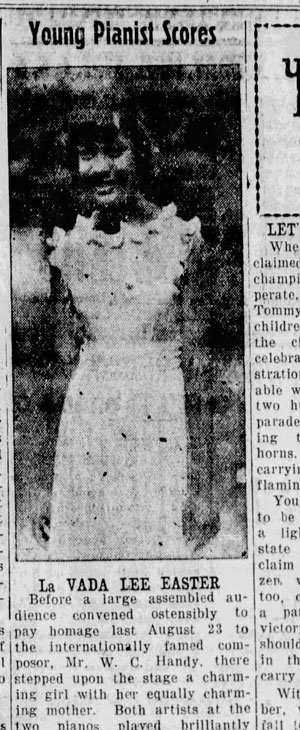

What led Stevens to dig beyond the scope of her original project was a newspaper article

from February 1940. That article reviewed a piano concert performed by Vada Lee Easter,

a talented “Webster College” student who was lauded as an incredibly gifted pianist

in the St. Louis region. The article included Easter’s picture and identified her

as Black. This would mean that Webster had a Black student enrolled in its programs

seven years earlier than its official policy change that integrated the campus. Photo: Vada Lee Easter in the Alton Telegraph in 1940.

What led Stevens to dig beyond the scope of her original project was a newspaper article

from February 1940. That article reviewed a piano concert performed by Vada Lee Easter,

a talented “Webster College” student who was lauded as an incredibly gifted pianist

in the St. Louis region. The article included Easter’s picture and identified her

as Black. This would mean that Webster had a Black student enrolled in its programs

seven years earlier than its official policy change that integrated the campus. Photo: Vada Lee Easter in the Alton Telegraph in 1940.

To double-check this information and make sure Webster wasn’t mentioned in error, Webster University turned to the Missouri Historical Society to search other public records for mentions of Easter. Jason D Stratman, with the Missouri Historical Society Library, found numerous articles from several newspapers that reviewed concerts performed by Easter. All identified her as a Webster College student.

Further research connected the pieces between the “official” history and Easter’s earlier enrollment. At the time, the music conservatory could directly admit students who showed incredible talent in their field, thus allowing Webster to enroll Black students without notifying Cardinal Glennon, Stevens said. “They could desegregate under the radar because they didn’t take out billboards announcing the change,” Stevens quipped.

Easter was a 13-year-old high school student at the all-Black Sumner High in 1936

when Webster Music Department Chair Sister Adaline Gemoets admitted her as an unofficial

part-time student to further hone her musical abilities. When Easter graduated from

high school in 1938, she officially enrolled as a part-time student at both Stowe

Teachers College (now Harris-Stowe University) and Webster. Webster’s records show

that she took classes in piano, harmony, ear training, keyboard harmony (theory) and

history of music, earning all A’s between 1938 and 1940. Her enrollment is further

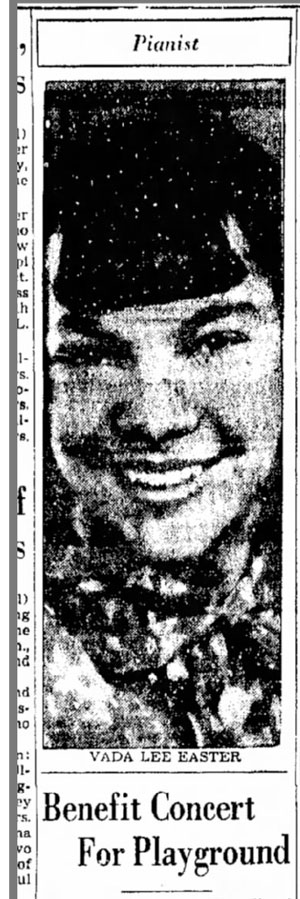

confirmed by newspaper articles in early 1940 that identify her as a Webster sophomore. Photo: Vada Lee Easter featured in the St. Louis Argus in 1937.

Easter was a 13-year-old high school student at the all-Black Sumner High in 1936

when Webster Music Department Chair Sister Adaline Gemoets admitted her as an unofficial

part-time student to further hone her musical abilities. When Easter graduated from

high school in 1938, she officially enrolled as a part-time student at both Stowe

Teachers College (now Harris-Stowe University) and Webster. Webster’s records show

that she took classes in piano, harmony, ear training, keyboard harmony (theory) and

history of music, earning all A’s between 1938 and 1940. Her enrollment is further

confirmed by newspaper articles in early 1940 that identify her as a Webster sophomore. Photo: Vada Lee Easter featured in the St. Louis Argus in 1937.

Newspaper articles also show that Easter frequently performed local concerts through 1940 while she attended Webster, and not just in St. Louis. Articles about her concerts were found in Texas, Pittsburgh, Detroit, and New York as she traveled the country to perform. Almost all identified her as a Webster student.

“It was a secret desegregation,” said Stevens. “I was reading Dr. Shannen Dee Williams' book ‘Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle’ (Duke, 2022) and noticed that she documented several instances of quiet desegregation already happening prior to the policy changes that lifted segregation at American universities. It appears that desegregation was happening on a local level long before it became a national issue.”

Part of the reason that Easter’s association with Webster may have become lost is

because she transferred to Fisk University when she was a junior in late 1940 and

never graduated from Webster, Stevens said. Webster’s records confirm that with a

notation that Easter had requested her transcript be issued on May 11, 1940, possibly

to be sent to Fisk. There, she completed her bachelor’s degree and went on to earn

a master’s and doctorate in Chicago, then had a distinguished career as a professor

at Howard University for over 30 years. Photo: Local newspaper announcement from 1942 announcing Vada Lee's graduation from

Fisk University.

Part of the reason that Easter’s association with Webster may have become lost is

because she transferred to Fisk University when she was a junior in late 1940 and

never graduated from Webster, Stevens said. Webster’s records confirm that with a

notation that Easter had requested her transcript be issued on May 11, 1940, possibly

to be sent to Fisk. There, she completed her bachelor’s degree and went on to earn

a master’s and doctorate in Chicago, then had a distinguished career as a professor

at Howard University for over 30 years. Photo: Local newspaper announcement from 1942 announcing Vada Lee's graduation from

Fisk University.

The Oblate Sister of Providence

While the new information shows that Webster officially enrolled a Black student much earlier than originally believed, other information was found that shed further light on the efforts to integrate local colleges. Both Stevens and the Missouri Historical Society uncovered numerous books, articles and other references to members of the Oblate Sisters of Providence — an all-Black Catholic religious community of nuns — taking classes at SLU, Webster and Maryville as early as the 1920s.

The Oblate Sisters staffed and ran St. Rita’s Academy for Colored Girls and the St. Francis Orphanage in Saint Louis in the early 20th century. In the mid-1920s, Missouri mandated that all teachers must earn a state-issued teaching certificate through a college, and that rule applied to all K-12 schools, including private schools such as St. Rita’s Academy. According to Shannen Dee Williams’ book “Subversive Habits” (2022), members of the Oblate order began taking summer classes at St. Louis’ Catholic colleges to meet those new state requirements.

Photo Courtest of Saint Louis University Archives — As published in the 1933 SLU yearbook,

it shows members of the Oblate Sisters posing with white nuns from other religious

orders in front of the School of Education.

Photo Courtest of Saint Louis University Archives — As published in the 1933 SLU yearbook,

it shows members of the Oblate Sisters posing with white nuns from other religious

orders in front of the School of Education.

Archival records at SLU show that Oblate Sisters M. Felix and Mary Laurentia Short were attending weekend classes at St. Louis University in 1928. Record also indicate that Sister Short was attending “regular sessions” of the University in 1934, indicating she was studying alongside regularly matriculated students of all races. Sister Short earned a bachelor’s in education from SLU in 1935. Photographic evidence in SLU’s archives also show that the Oblate Sisters were studying alongside white nuns from other orders as early as 1933 — an integrated environment.

In 1938, Maryville allowed members of the Oblate Sisters to attend classes on Saturdays as well for state certification purposes, but their records do not indicate if other non-Black students studied alongside them.

A newspaper article from the “Webster News” in 1941 said the Oblate Sisters took classes at Webster alongside nuns from numerous other orders, as well as regularly matriculated students from 10 other states, confirming that Webster’s summer classes were desegregated and that the nuns studied alongside regularly enrolled students and not just members of other religious orders. This further suggests that Webster had integrated classroom environments six years earlier than its “official” desegregation policy.

Unanswered Questions

Was Easter the only Black student at Webster University before 1947 who was not a member of a religious order? While researching her past, Stevens came across a photo of Easter along with another Black musician, Rosalyn Harris Ball England-Henry. England-Henry was only a few years younger than Easter and was another talented musician who, according to the newspaper clipping, was studying music at Webster University in 1945. Her obituary also identified her as a former Webster student, thus confirming that she too attended classes before Webster “officially” integrated. Additionally, Stevens also came across other clippings that indicate that Thomas – the student who is listed in history books as one of Webster’s first two “official” Black student — was attending classes in 1946, one year before the “official” desegregation policy was announced.

“What we can deduce is that the opposition to Foster (the student Glennon ordered to be expelled from Webster because she was Black) was a surprise to the sisters, but it didn’t keep the music department from recognizing and teaching talented students, regardless of their race or ethnicity,” Stevens said. “Was Easter Webster’s first Black student? She may have been but because the records are not complete, we cannot say for sure. There may have been others before her.”

What This Says About Our Understanding of History

SLU was the first institution of higher education to officially announce a desegregation policy in Missouri, but the story is much more complex than that. The integration of college campuses in the St. Louis region started decades earlier, and often at the departmental level — whether it was SLU, Maryville and Webster offering educational courses in an integrated environment to the Oblate Sisters or if it was Webster officially admitting Easter as a music student in 1938. All this suggests that the announcements of a desegregation policy happened after integration had already started, and that it didn’t just occur overnight with an official decree.

“What we have learned is that desegregation did not start with policy changes, but rather was spurred on by different types of grassroots movements and the actions of individuals at each of the institutions which then caused the institutions to adapt,” Stevens said. “What matters is that we have an accurate understanding of what happened, how it happened, when it happened and how that has led us to this moment in time, because it gives us more context and better advises us on what we can do to keep moving forward.”

And that is what is irritating about recent actions by officials to prevent Black history from being taught in schools, Flewellen said. By banning the discussion of what happened in Black communities, those officials are preventing the discovery of stories such as that of Vada Lee Easter and the priest, nuns and community members who broke the rules to right a wrong.

“What is frustrating is that there is a concerted modern movement to keep Black history buried under the notion that teaching about the very real inequities in the United States is somehow unpatriotic or unhealthy to the egos of non-Black students,” Flewellen said. “Some have claimed that further study will reveal even more horrors and harm that were inflicted on people of color in this country, but that such information would cause discriminatory behavior against white people. Yet in the story about Vada Lee Easter, we have uncovered evidence that organized groups of white priests and nuns were defying the Church and societal norms at the time and quietly enrolling Black students nearly two decades before the issue of desegregation was struck down by the courts. In the end, this shows that by diminishing Black history, we are diminishing U.S. history.”

Editor’s Note: Webster University reached out and heard back from officials at Howard University, SLU, Maryville, Fisk and the Missouri Historical Society for comments for this story. Those who provided feedback were given opportunities to correct or add information to the story. Webster University appreciates the efforts of officials at all the institutions who responded and their assistance in making this story as accurate as possible.